Development of Eye

- teachanatomy

- Jul 4, 2025

- 9 min read

Organs of Special Sense are organs specialized in perceiving sensory information. They include the eyes, ears, the nose and the tongue. The eyes are organs of sight that contain specialized sensory cells that perceive light, shape of objects and colour; they transform light into electrical signals that are interpreted by the brain. The ears are responsible for hearing and balance. They have a cochlear auditory system responsible for hearing and a vestibular system responsible for balance. The contains the olfactory mucosa that comprises sensory olfactory cells specialized in sensing smell and generate impulses that are interpreted by the brain. The tongue has several functions that include sensing taste. It contains specialized structures called taste buds that contain sensory cells and nerve ending specialized in identifying different tastes. The nose and tongue have already been covered in previous chapters (respiratory system and digestive system chapters), thus this chapter will deal only with the development of the eyes and ears. Organs of special senses start to show up during the early stages of embryonic development.

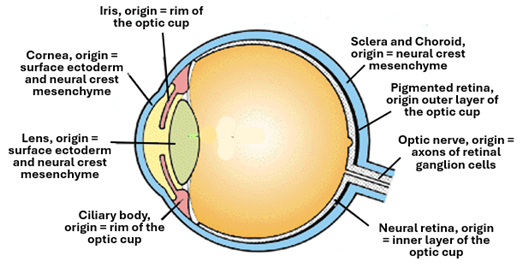

Development of the Eye

The eye development begins early in about the 3rd week of embryonic development and continues for a longtime thereafter. Its sensory components are ectodermal developing from the neural tube ectoderm. The first step in development of the eye is the formation of a pair optic vesicles, each as a lateral evagination of the neuroepithelium forming the wall of the caudal part of prosencephalon, the first of the primary brain vesicle. Later on, when the prosencephalon divides into two secondary vesicles, the optic cup remains connected to the diencephalon, the second one of the secondary brain vesicles. The optic vesicles enlarge, and their distal ends expand and approach the surface ectoderm (the head ectoderm). The distal part of the extended part of the optic vesicle invaginates on itself thus transforming the vesicle into a double-walled cup-shaped structure called the optic cup. The optic cup remains connected to the diencephalon via a connecting stalk called the optic stalk. The optic cup differentiates into the retina of the eye, whereas the optic stalk participates in the formation of the nerve. The optic cup induces the overlying head ectoderm to proliferate and form a thickening called the lens placode which gradually transforms into a vesicle called the lens vesicle. The lens vesicle then detaches itself from the general ectoderm and sinks to settle in between the rims of the optic cup where it differentiates into the eye lens. The lens vesicle after detaching from the ectoderm, induces the overlying ectoderm to differentiate into the cornea of the eye. Thus, the retina and the optic nerve are of neuroectoderm origin, whereas the lens and cornea of general head ectoderm origin. The other parts of the eye including the sclera, choroid, iris, ciliary body and processes are all of neural crest mesenchyme origin and thus are also of ectoderm origin. Neural crest cells originating from the peripheries of neural folds migrate into the head region and develop into mesenchymal cells.

Development of the Retina

The adult retina has two main parts, the nervous retina (neural retina) and the pigmented retina. The nervous retina develops from the inner layer of the optic cup, whereas the pigmented retina develops from the outer later of the optic cup.

The pigmented retina also called the retinal pigmented epithelium is a single layer of cuboidal cells that contains numerous pigment granules. It developed from the outer layer of the optic cup under the influence of signaling factors such as FGF and MITF. The component cells are phagocytic cells that eliminate worn out rods and cones.

The nervous retina (neural retina) is a highly complicated layer responsible for light reception and generation impulses that are transmitted via the optic nerve to the CNS for interpretation. The differentiation of the neuroepithelium of the multilayered retina is controlled by a wide array of genes and signaling biomolecules. The nervous retina contains several types of neurons and supporting cells which include the photoreceptor cells, the bipolar cells, the ganglion cells, the amacrine cells and Muller cells, which all differentiate from the retinal progenitor cells of the inner layer of the optic cup. Thus, the retinal progenitor cells are multipotent cells capable of giving rise to several types of functional cells. They differentiate in an orderly manner first giving rise to cone photoreceptor cells and ganglion cells first, then giving rise to bipolar cells and rod photoreceptor cells.

The photoreceptor cells, the bipolar cells and the ganglion cells arrange themselves into layers. The axons and dendrites of these three types of cells approach each other and synapse forming the plexiform layers. Ultimately, the nervous retina (neural retina) shows it distinct eight layers which are as follows from inside outwards:

Layer of rods and cones (of photoreceptor cells).

Inner nuclear layer (nuclei of photoreceptor cells).

Inner plexiform layer (axons of photoreceptor cells and dendrites of bipolar cells).

Outer nuclear layer (nuclei of bipolar cells).

Outer plexiform layer (axons of bipolar cells and dendrites of ganglion cells).

Ganglion cell layer (cell bodies of ganglion cells).

Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of ganglion cells).

The functioning of the retina depends on the three sets of the three cells connected to each other by synapses. The first set of cells (the photoreceptor cells) sense light and pass electrical signals via axodendritic synapses to the second set of cells (the bipolar neurons), which transmit the signals via another set of axodendritic synapses to the third set of cells (the ganglion), which transmit the signals to brain via their axons. Two types of horizontally oriented neurons make coordination of the activities of these three sets cells; these are the horizontal S-potential cells and the amacrine cells. All five types of cells, in addition to supportive cells called Muller cells, develop from the retinal progenitor cells.

The optic nerve develops from the optic stalk, which connects the optic cup to the diencephalon. During transformation of the optic vesicle into the optic cup a groove is formed in the optic stalk; this groove is called the choroid fissure. The fissure allows the passage of hyaloid vessels which later known the central retinal vessels. Axons of the retinal ganglion cells form the retinal nerve fibers which run towards the diencephalon within the choroid fissure forming the optic nerve. Thereafter the choroid fissure closes investing the hyaloid vessels and the optic nerve.

Development of the Lens

The lens develops from the general head ectoderm overlying the optic vesicle. The optic vesicle induces the overlying surface ectoderm to proliferate and thicken forming the lens placode. The placode invaginates into a pit a then into a vesicle called the lens vesicle which sink into the underlying mesenchyme, then loses connection with the surface ectoderm. In the meanwhile, the optic vesicles has transformed into the optic cup. The lens settles between the rims of the optic cup. There the ectodermal epithelial cells of the vesicle differentiate into lens cells including lens fibers and stem cells. The posterior cells of the lens vesicle elongate into columnar cells, lose their nuclei, lose their organelles, deposit crystallin, become transparent, and form the primary lens fibers. The primary lens fibers increase in number and fill the lumen of the lens vesicle and contribute to the lens nucleus. The secondary lens fibers differentiate from the epithelium surrounding the primary lens fibers anteriorly. They gradually surround the primary lens fibers completely. The anterior cells of the lens vesicle arrange themselves into a single layer of cuboidal cells forming the lens epithelium. The lamina surrounding the lens vesicle differentiate into the lens capsule.

Development of the Cornea

The cornea is a transparent structure covered anteriorly by the corneal epithelium and posteriorly by the corneal endothelium, and in between is a connective tissue substantia propria. The newly formed lens vesicle induces the overlying surface ectoderm to proliferate and thicken forming the corneal placode. The corneal epithelium, which is a stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium develops from the lens placode, whereas the underlying mesenchyme, which is of neural crest origin, differentiate to give rise to the corneal endothelium and corneal stroma which is known as the substantia propria.

Development of the Uvea

The uvea, which is also known as the vascular tunic of the eye, is middle tunic of the eye inter is positioned between the nervous tunica (the retina) and the fibrous tunic (the sclera). It has three parts known as choroid, ciliary body and iris.

The choroid similar to many other structures in the eye, is of neural crest origin. Cells of the neural crest originating in the region of the cranial parts of the neural tube, migrate throughout the head region differentiate into head mesenchyme and contribute to the formation of several head structures. The neural crest mesenchyme surrounding the developing optic cup differentiate into connectives tissues and smooth muscle fibers that makes the various parts of the uvea including the choroid, ciliary body and the iris. In the 4th week of embryonic development, the choroid appears as a loose connective tissue. By the 6th week several blood vessels appear within this connective tissue rendering it into a vascular layer.

In the 5th week of embryonic development, the ciliary body begins to develop from the distal parts of the optic cup and the surrounding neural crest mesenchyme. The epithelium originates from the ectoderm of the rim of the optic cup, whereas the ciliary muscle and stroma are of neural crest mesenchyme origin. It folds to form the ciliary processes. The epithelium differentiate into two layers, a pigmented layer and a nonpigmented one. The pigmented layer continues with the pigmented layer of the retina, whereas the nonpigmented one continues with the nervous (neural) retina. The ciliary body has three main functions which are production of the aqueous humor, lens support by its suspensory ligaments, and lens accommodation and focusing by contraction and relaxation of the ciliary smooth muscle fibers. Similar to the ciliary body, the iris develops from the rim of the optic cup and the surrounding neural crest mesenchyme.

The sclera develops from the neural crest surrounding the developing eye. The process starts at about the 6th week of embryonic development. It develops from the mesenchymal cells surrounding the developing choroid. These cells differentiate into fibroblasts that synthesis collagen fibers, elastic fibers and elements of the ground substance. The tissue condense into a dense fibrous protective connective tissue investment called the fibrous tunic of the eye. The sclera connects anteriorly with the cornea at the limbus. Posteriorly the sclera continues with dura mater, the outer layer of the meninges.

The eye reaches full structural development by the 36th week of gestation. However, the brain is not yet capable of fully processing the visual information, and the vision continues to improve over the 3 or 4 years of postnatal life.

Congenital Anomalies of the Eye

Several developmental abnormalities affect the eye; they include anophthalmia, microphthalmia, coloboma, aniridia, congenital glaucoma, and congenital cataract. The anomalies are often caused by genetic mutations and exposure to teratogenic drugs, chemical and infectious agents. The anomalies cause vision problems, and abnormal appearance.

Anophthalmia is the total absence of the eyeball leading to blindness; it results from failure of development of the optic vesicle, or arrest of the eye development at optic vesicle stage, whereas microphthalmia is a condition where the eye is unusually small eye which often results from failure of normal growth of the optic cup.

Coloboma is an anomaly of the eye where some eye structures are missing at birth; it is caused by failure of closure of the choroid fissure. Coloboma may affect the iris, retina, the choroid or the optic nerve, where parts of the above structures are missing.

Aniridia is an anomaly where the is partially or completely missing, causing reduced vision acuity and increased sensitivity to light. Abnormalities of the iris cause abnormalities in size (quite large) and shape of the pupil.

Congenital Glaucoma is caused by abnormal development of the eye limbus causing build up of the aqueous humor and increased intraocular pressure that may cause damage of the optic nerve and loss of vision. It may also cause retinal detachment and impairment of vision.

Congenital Cataract is a birth defect where the lens is cloudy or opaque at birth thus causing vision impairment. It is caused by factors affecting the normal development and transparency of the lens. These factors often disrupt the process of development of the lens vesicle and transformation of the epithelium of its posterior wall into secondary lens fibers.

Comments