Female Reproductive Development

- teachanatomy

- Jul 5, 2025

- 17 min read

Updated: Jul 9, 2025

The main functions of the male and female reproductive systems include the production of gametes, secretion of sex hormones (e.g. estrogen, progesterone and testosterone), providing a safe site for fertilization and development of the embryo and fetus, nourishment of the developing embryo and fetus, giving birth to a newborn at the end of gestation, and breastfeeding the newborn after birth. All of these functions excluding the production of male gametes (sperms) and male sex hormone (testosterone) and carried out by the female reproductive system. The male reproductive system produces enormously large numbers of motile gametes (sperms) on a daily basis compared to much fewer nonmotile female gametes (egg cells) that diminish in number with age and at the end are lost altogether. After puberty, the female reproductive system undergoes periodic functional changes; such periodic changes do not occur in the male reproductive system.

The female reproductive system is occasionally referred to as the female genital system. It consist of a group of organs and structures that work together to enable pregnancy, and childbirth. These organs include: the ovaries, the Fallopian tubes, the uterus, the cervix, the vagina, the external genitalia, and the mammary glands.

The female reproductive system has several functions which include:

Production of female sex hormones, namely estrogen and progesterone.

Production of ova, the female gametes.

Facilitation of union of gametes i.e. fertilization of the ovum by a spermatozoan.

Transport of the zygote (the fertilized ovum) from the fallopian tube to the uterus.

Facilitate implantation of the blastocyst in the uterine endometrium.

Formation of the placenta and maintenance of the embryo and the fetus during the entire period of gestation.

Birth of the newborn and expulsion of the placenta during labour.

Production of milk to feed the newborn.

The female Gonad

The ovary is the female gonad that produces the female gametes or ova. There are two ovaries in females, one on each side of the uterus. Each ovary is an oval structure, about 6cm long in mature normal women, yet they diminish in size after menopause. Structurally, the ovary consists of an inner medulla, an outer cortex and a connective tissue capsule. In the peritoneal aspects of the ovary, the capsule itself is covered by a single layer of mesothelial cells, often referred to as the mesothelium or germinal epithelium. The ovary has a hilum, which is a shallow surface depression. The hilum is the site of entrance of blood vessels and nerves into the ovary. Embryologically, the ovary is of mesodermal origin; it develops from the gonadial ridge of the mesoderm. The ovarian capsule is a dense irregular connective tissues made of connective tissue fibers and cells; the fibers are predominantly collagen type-1 fibers. Beneath the mesothelium covering the capsule there is a thin condensed connective tissue layer known as the tunica albuginea.

The ovarian cortex is histologically characterized by the presence of various types of ovarian follicles, which include primordial follicles, primary follicles, secondary follicles, tertiary follicles and mature Graafian follicles, in addition to degenerate atretic follicles and corpora lutea. In between the follicles there is a supportive connective tissue containing large numbers of stromal cells.

The ovarian medulla is primarily made of a loose connective tissue rich in blood vessels and nerves; these vessels and nerves gain access to the medulla via the ovarian hilum. A conspicuous feature of the ovarian medulla are numerous spiral arteries, which as known as the helicine arteries. Branches of these spiral arteries emerge and pass into the cortex supplying the cortical tissues. Activities of the ovaries are modulated by the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which both produced by the pituitary gland.

The Ovarian Follicles

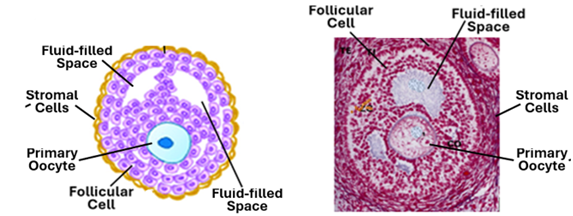

Baby girls are born with their ovarian cortex containing about 1-2 million primordial follicles, each ovary containing about 500,000 to 900,000 follicles. The primordial follicle consists of a single primary oocyte surrounded by a single layer of flat follicular cells. At the onset of puberty, the pituitary gland begins to release the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which initiates the development of primordial follicles. The release of FSH is periodical and accordingly there are periodical waves of development of primordial follicles. Each month, under the influence of FSH a cohort of about 20 primordial follicle are recruited for development. To begin with, the follicles enlarge due to the enlargement of the follicular cells, which change shape from flat cells into cuboidal cells or low columnar cells. Then, the follicular cells become more responsive to FSH, and start to proliferate forming two, three and more follicular cells layers around the primary oocyte. In this way the recruited primordial follicles develop into primary follicles and then into secondary follicles. A follicle with a single layer of cuboidal follicular cells is called a primary follicle, whereas a follicle with more than one layer of follicular cells is called a secondary follicle. At the same time, the primary oocyte enlarges and becomes separated from the surrounding follicular cells by a clear homogenous eosinophilic membrane called the zona pellucida. Still under the influence of FSH, the follicular cells start to secrete estrogens and fluids containing estrogen starts to build in between the follicular cells. Eventually, fluid-filled vesicles appear amongst the follicular cells. When the fluid-filled spaces are present amongst the follicular cells, the ovarian follicle is referred to as a tertiary follicle or early antral follicles.

Often, the ovarian follicles are classified into antral and preantral follicles. An antral follicle is a follicle that contain a large single fluid-filled cavity known as the antrum. A preantral follicle does not have an antrum; it may contain multiple small fluid-filled spaces. Preantral follicles like antral follicles are surrounded by a theca layer. Theca layers develop from the stromal cell that surround the growing follicle. The stroma cells arrange themselves around the developing follicle delineating it from the surrounding tissues. The process of formation of the theca layer commences in the secondary follicle stage and becomes more and more evident as the follicles develops, becoming more prominent in tertiary follicles. The tertiary follicle is a preantral follicle consisting of primary oocyte surrounded by a clear zona pellucida, follicular cells containing flues filled spaces and a clear stromal cell investment referred to the theca folliculi.

The Antral Follicle

The fluid-filled cavities of tertiary follicles coalesce to form a single large cavity called the antrum. A follicle that possess an antrum is known as the antral follicle. The antral follicle continues to enlarge, and when it reaches a diameter of 0.5mm it is called a Graafian follicle. The Graafian follicle or the mature follicle releases its oocyte at the time of ovulation. The fluid contained within the antrum is called the follicular fluid or the liquor folliculi. The mature Graafian follicle is a well differentiated structure. It is characterized by a large clearly defined antrum full of liquor folliculi. The layers of follicular cells that surround antrum constitute what is known as the stratum granulosum. Follicular cells that immediately surround the oocyte elongate, become columnar in shape and appear as if they are radiating from the oocyte; this single layer of radiating follicular cells constitute the corona radiata. A prominent homogenous eosinophilic zona pellucida separates the oocyte and the corona cells. The accumulation of cells that anchor the oocyte and the corona cells to the rest of follicular cells is called the cumulus oophorous. A well-developed theca folliculi invests the whole Graafian follicle. The theca folliculi comprises two layers; a more cellular theca interna and a more fibrous tunica externa. Theca interna cells are endocrine cells that produce a steroid hormone called androstenedione. Granulosa cells take up androstenedione from the theca cells and transform it into estrogen. Granulosa cells also produce small amounts of follicular FSH and inhibin. A thick basement membrane separates theca interna from the stratum granulosum; this membrane is known as the glassy membrane. Theca interna cells are cuboidal or thick ovoid cells. In addition to androstenedione, they produce small amounts of progesterone. The theca externa cells are spindle-shaped cells similar to stromal cells; they have contractile abilities, and by their contraction they help in the process bursting of the follicle and release of the oocyte at the time of ovulation. The primary oocyte of Graafian follicle completes the first meiotic division just before ovulation, releasing a polar body and become a secondary oocyte.

Corpora Lutea and Albicans

Each month, several primordial follicles become responsive to FSH and begin to develop into primary follicles, then to preantral follicles and finally to antral follicles. Of these cohort of developing follicles, only one follicle reaches the stage of ovulation, the rest of the cohort follicles undergo apoptosis at various stages of their development. Prior to rupture of the mature Graafian, its primary oocyte completes the first meiotic division, releases a polar and becomes a secondary oocyte. Under the influence of the pituitary LH, the granulosa and theca interna cells of the ruptured Graafian follicle transform into pigment containing and progesterone producing endocrine cells known as luteal cells. Luteal cells are of two types: large granulosa luteal cells and smaller theca luteal cells. They both produce progesterone and smaller amounts of estrogen. At the early stages of the formation of the corpus luteum blood from ruptured vessels fill the antral cavity. Such a structure containing blood in its antral cavity is called corpus hemorrhagicum. The corpus luteum persists after fertilization as a corpus luteum of pregnancy. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum will regress by the end of the menstrual cycle.

Atretic Follicles and Corpora albicans

Follicles that do not reach maturity undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death) and become atretic follicles. Atretic follicles are made degenerate cells and often show an abnormally thick glassy membrane When a corpus luteum regresses, particularly the corpus luteum of pregnancy, it leaves a prominent scar tissue structure known as the corpus albicans.

Fallopian Tubes

The fallopian tubes are also known as the uterine tubes and oviducts. Each of the two Fallopian tubes is about 10cm long. The Fallopian tube is a channel for transportation of the ovum from the ovary towards the uterus. It is the site of fertilization where the union of gametes takes place; it also transports the fertilized ovum (the zygote) towards the uterus. Anatomically the Fallopian tube is divided into four parts, which are the infundibulum, ampulla, the isthmus, and the intramural part. The infundibulum is the widened funnel-shaped initial part that lies adjacent to the ovary, partly covering the ovarian surface with its finger-like projections. The ampulla is middle; it is the part where fertilization usually takes pales. The isthmus is the part connected to the uterus and continues within the uterine wall form the intramural part of the Fallopian tube. Histologically, the wall of the Fallopian tube wall consists of three tunics: the tunica mucosae, the tunica muscularis and the serosa. The mucosa consists of an epithelium and the underlying lamina propria. The tubal epithelium is simple columnar epithelium but often appears pseudostratified in some regions due to presence of few basal cells. Here, it contains three types of cells: columnar ciliated cells, secretory cells and intercalated cells. The ciliated cells are more numerous in the infundibulum and neighboring parts of ampulla. By the rhythmic movements of their cilia, the ciliated cells help in transporting the ovum towards the uterus. The secretory cells are tall columnar non-ciliated cells that secrete more actively at the time of ovulation. Secretory cells are more numerous in the ampulla and the isthmus. The secretion produced by these cells facilitates movement of sperms, participates in the transport of ova and zygotes, and provides nutrients to the fertilized ovum. The intercalated cells, which are also known as peg cells, are secretory cells that produce substances that capacitate sperms (making them capable of fertilizing the ovum). The lamina propria of the fallopian tube is a highly cellular connective tissue. It contains numerous spindle-shaped cells along with fibroblasts and thin collagen fibers. It is devoid of glands but the highly branching mucosal folds may give the impression of glandular mucosa, particularly in the ampulla where the folds are prominent and complicated. The tubal tunica muscularis become progressively thicker towards the uterus. It consists of a well-developed inner circular layer and a thinner outer longitudinal layer; both of these layers are made of smooth muscle fibers. Their contractions produce peristaltic movements that assist in the transport of the ovum towards the uterus.

The Uterus

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ located within the female pelvis. It has several functions that most importantly include nourishment and protection of the embryo and the fetus. It is where embryo implantation and fetal development take place. It has four region: the fundus, the body, the isthmus and the cervix. It has a thick wall that consists of the endometrium, myometrium and epimetrium. The endometrium is the tunica mucosae of the organ, the myometrium is its tunica muscularis, and the perimetrium is the serosa.

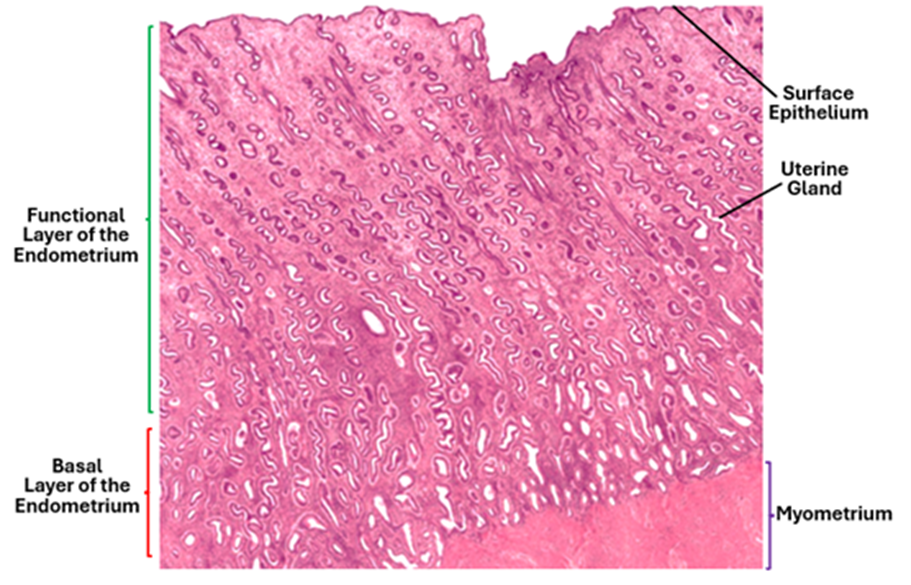

Endometrium

The endometrium is the innermost layer of the uterine wall; it is made up of an epithelium and the underlying lamina propria. The uterine epithelium is simple columnar epithelium with sporadic ciliated cells. The lamina propria is highly cellular, containing many spindle shaped cells known as the decidual cells. The decidual cells are secretory; they secrete small amounts of prostaglandins and fibrinolysin. The lamina propria contains simple tubular glands known as the uterine glands. The endometrium comprises two layers: an upper functional layer and a deep basal layer. The functional layer is divided into a superficial compact zone and a deeper spongy zone or layer. The functional layer is sloughed off during menstruation and lost. The basal layer remains unaffected by the menstrual cycle.

Under the influence of female sex hormones (estrogen and progesterone), the endometrium undergoes cyclic changes. During messes, the inner layer of the endometrium, which is called the functional layer or the stratum functionalis, is sloughed off and lost. During the follicular phase, the endometrium under the influence of estrogen proliferates and regenerates from the basal layer or the stratum basalis. This phase is known as the proliferative phase of the endometrium. In the following phase which is the luteal phase and under the influence of progesterone, the uterine glands become tortuous and highly secretory; this phase is known as the secretory phase of the endometrium.

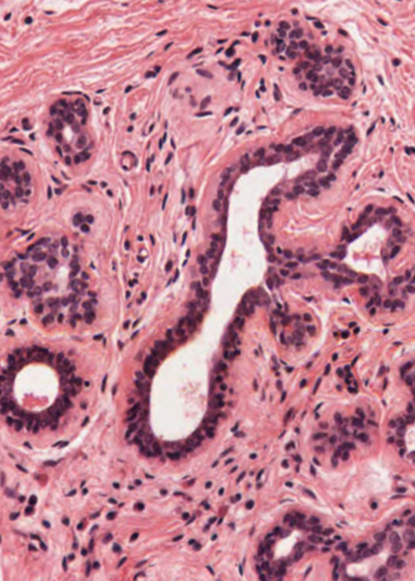

The first phase of the cycle is the proliferative phase where development of endometrial gland takes place under the influence of estrogen. This phase lays down a foundation for the subsequent reproductive phases if pregnancy takes place. The proliferating glands show signs of epithelial cell divisions and multiplication. The glandular epithelium often appears pseudostratified, the glandular lumen remains undiluted and the stroma is highly cellular.

The second phase is the secretory phase, where the uterine glands produce a secretion rich in nutrients; the secretion is released into the uterine lumen to nourish the incoming fertilized ovum and the embryo before implantation. In this phase the uterine glands become highly coiled, taking a corkscrew appearance. Coiling of the glands greatly increases the epithelial cell surface area available for secretion. As more and more secretion pass from the secretory cells into the lumen. the lumen become wider and wider. Glandular cells synthesize and secrete glycogen. Glycogen particles accumulate in the cytoplasm of glandular epithelial especially in the basal parts. Glycogen is water soluble and is washed out during routine histological preparations, therefore the glandular secretory cells at this phase appear pale or foamy. This phase is maintained by high levels of progesterone.

Uterine Vasculature

Branches of the uterine artery pass into myometrium and form arcuate arteries which supply the smooth muscle fibers of the myometrium. Radial arteries originate from arcuate arteries and pass towards the endometrium. The basal layer of the endometrium is supplied by straight short basal arteries whereas the functional layer of the endometrium is supplied by the spiral helicine arteries. Decline in ovarian hormones causes constriction of the helicine arteries leading to ischemia of the functional. As a result, this layer is sloughed off causing menses.

The Cervix

The uterine cervix is the lower narrow end of the uterus that connects the uterus to the vagina; it is a muscular, tunnel-like organ about 2-3cm long. The cervical wall consists of a mucosa made up of an epithelium and the lamina propria and the muscularis which is made of smooth muscle fiber, surrounded by an adventitia.

The cervix has two parts: the endocervix (cervical canal) and ectocervix, the endocervix and the external os. The endocervix which is also known as the cervical canal, is lined by simple columnar epithelium, whereas the external os, which is also known as ectocervix is lined by stratified squamous epithelium.

Lamina propria is collagenous connective tissue. The surface epithelium invaginates into the lamina propria in the form of furrows or clefts that appear in histological sections as if they are simple tubular glands. The epithelial cells are secretory cells that produce mucus. The activity of these glands and consistency of their secretion are influenced by the ovarian sex hormones.

The Vagina

The vaginal wall is made of a mucosa, muscularis and adventitia. The mucosa has folds known as rugae and is lined by a stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium. The lamina propria rich in elastic fibers and is devoid of glands. The muscularis is made of smooth muscle and the outermost layer is the adventitia which made of a collagenous connective tissue.

The Mammary Gland

The mammary glands, often referred to as the breast, are essentially compound tubuloalveolar glands. They are highly modified apocrine sweat glands that develop from the general embryonic ectoderm. The breasts of both males and females develop in a similar fashion from birth to puberty. At puberty the female breast enlarges under the influence of hormones secreted by the pituitary and ovaries, primarily due to epithelial cell proliferation and adipose tissue deposition. The breast of adult women undergoes cyclic changes under the influence ovarian hormones until menopause. After menopause, the breast undergoes progressive atrophy and involution. The primary function of the female mammary glands is the production of milk for nourishment of the newborn.

Structural Features

Each of the two breasts consists of 15 to 25 independent units called the breast lobes. Each lobe contains a compound tubulo-alveolar gland. The size of the lobes is variable. A lobar duct emerges from each of the larger lobes and passes towards the breast nipple. Before opening onto the nipple surface, each of the lobar duct forms a dilatation called the lactiferous sinus. Smaller lobes have in blind-ended ducts that do not reach the nipple surface.

The breast has a large amount of adipose tissue that constitutes a significant portion of the breast fat pad. The variation in breast size amongst women is related to the adipose tissue volume rather than the epithelial glandular component itself. The breast adipose tissue is abundant in the interlobular spaces and scarce within lobules. Breast lobes are embedded in a mass of adipose tissue, subdivided by collagenous septa. The adipose tissue actively participates in mammary gland homeostasis and milk production.

The breast stroma is a loose connective tissue made of a ground substance, connective tissue fibers and different types of connective tissue cells. The ground substance contains proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid and fibronectin, whereas the fibers are primarily type-1 and type-3 collagen fibers. Fibroblasts are the most common type of cells in the breast stroma; they are the source of the ground substance and fibers.

The nipple is traversed by lactiferous ducts (milk ducts) surrounded by bands of smooth muscle, oriented parallel to the lactiferous ducts; at the nipple base the smooth muscle fibers are circularly near the base. Contraction of these muscle bands causes erection of the nipple. The nipple shows numerous surface orifices; these are the openings of the lactiferous ducts. The nipple is surrounded by a circular pigmented area of skin known as the areola. The areolar skin is subject to change in colour (darkening) during pregnancy. The peripheral regions of the areola contain several nodular elevations known as tubercles of Morgagni, which contain the openings of Montgomery glands. These glands are modified glands that represent an intermediate stage between sweat and true mammary glands. They secrete a substance that provides lubrication during breastfeeding.

Within each lobe of the breast, the lobar duct branches repeatedly to form a number of terminal ducts, each of which leads to a lobule consisting of several alveoli. The lobules are separated by moderately dense collagenous interlobular tissue, whereas the intralobular supporting tissue surrounding the ducts within each lobule is less dense and more vascular.

The ducts and the acini are lined by two layers of epithelial cells, i.e. a bistratified epithelium. The luminal epithelial cells of the large ducts are columnar cells, whereas those of the smaller ducts are cuboidal. Thus, larger ducts are lined by a stratified columnar epithelium, whereas the smaller ones are lined by a stratified cuboidal epithelium. A layer of myoepithelial cells present around the ducts helps to expel milk out of the lobules towards the lobar ducts and lactiferous sinus. The epithelium of the lactiferous sinuses is similar to that of lobar ducts. Close to the surface the epithelium of duct system transforms into a stratified squamous epithelium.

The Breast during pregnancy and Lactation

The mammary glands undergo significant structural changes during pregnancy in response to lactogenic hormones produced by the pituitary gland, the placenta and the ovaries; these hormones are prolactin, human chorionic somatomammotropin, estrogen and progesterone. Under the influence of these hormones the duct epithelium proliferates forming new ducts and secretory acini. The breast lobules increase in size at the expense of the interlobular connective tissues. The lining epithelial cells vary from cuboidal to low columnar. As pregnancy progresses, the acini begin to secrete a protein-rich fluid called colostrum, the accumulation of which causes dilation of the acinar lumen. As compared to milk, colostrum contains little lipid. Colostrum is the first form of breastmilk that is released by the mammary glands after giving birth. It is rich in nutrients, has as high content of antibodies and antioxidants that help to build the immune system of the newborn. It gradually changes into breast milk within two to four days of delivery of the newborn.

After parturition, progesterone levels decrease, lifting its inhibitory effect over prolactin, and prolactin stimulates copious milk secretion in conjunction with oxytocin. The lactating breast is composed almost entirely of acini distended with milk, and the interlobular tissue is reduced to thin interlobular septa. The acini appear under the microscope filled with an acidophilic substance with vacuoles; milk proteins stain acidophilic and the vacuole are lipid droplet that dissolved during tissue processing. The epithelial cells are flattened and the acini distended by secretions. A neurohormonal reflex, initiated by suckling, causes the release of the hormone oxytocin from the pituitary. Oxytocin causes contraction of the myoepithelial cells which surround the secretory acini and ducts, thus squeezing milk out of the lobules into the lactiferous sinuses; this is known as milk-let-down. After weaning, withdrawal of the suckling stimulus, and the associated release of pituitary hormones causes regression of the lactating breast and resumption of the normal ovarian cycle.

QUICK QUIZ

1. In which of the following females do you expect to find the ovarian cortex devoid of ovarian follicle?

A. A newly born baby girl.

B. A 7-years-old girl.

C. An 18-year-old girl.

D. A 32-years-old pregnant woman.

E. A 66-years old widow.

2. Which of the following structures synthesizes progesterone?

A. Theca interna.

B. Theca externa.

C. The corpus albicans.

D. The atretic follicle.

E. The corpus luteum.

3. The secondary ovarian follicle is characterized by which of the following?

A. A single layer of flat follicular cells.

B. A secondary oocyte.

C. An antrum.

D. Two layers of follicular cells.

E. A prominent theca externa.

4The luteal phase endometrium is characterized by which of the following?

A. Absence of glands in the functional layer.

B. Absence of glands in the basal layer.

C. Loss of surface epithelial cells.

D. Short straight endometrial glands.

E. Long tortuous endometrial glands.

Comments