Digestive Development

- teachanatomy

- Jul 4, 2025

- 20 min read

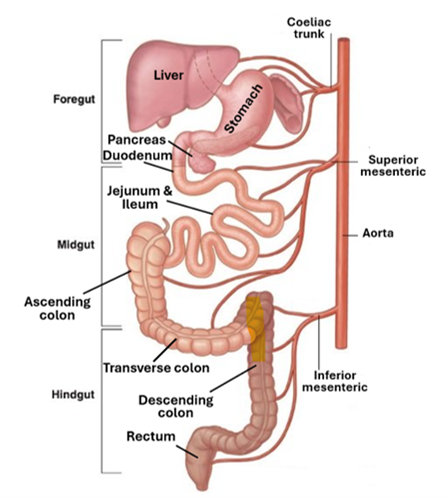

The development of the digestive system involves the formation of the gastrointestinal tract and the associated organs, namely the liver, pancreas and the salivary gland. The process has two main phases, an embryonic phase development and organogenesis.

The embryonic phase development comprises gastrulation, formation of the endoderm, and formation of the gut. During gastrulation, the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) are formed. The thus formed endoderm forms the lining of the primitive gut, which comprises the foregut, the midgut and the hind gut. This endodermal lining forms the surface epithelium lining the alimentary tract, the glandular epithelium of the digestive intramural glands, and the parenchyma of the liver and the pancreas.

During organogenesis the esophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, the liver, and the pancreas develop from the foregut, the jejunum and the ileum from the midgut, and the large intestine from the hind gut. This is accompanied by rotation and fixation of the alimentary tract and recanalization of the digestive tube.

Development of the digestive system occasionally yields congenital anomalies such as esophageal atresia, intestinal atresia, and intestinal atresia.

The Primitive Gut

As a result of the embryo’s cephalocaudal and lateral folding, part of the yolk sac is incorporated into the embryonic body to participate in the formation of the primitive gut. Two other endoderm-lined parts, the definitive yolk sac and the allantois, remain outside the embryonic body as extraembryonic sacs. In the cephalic part of the embryo, the primitive gut forms a blind-ended tube that forms the foregut; similarly, a blinded-ended tube in the caudal parts of the embryo forms the hindgut. The part in-between the foregut and the hind gut is the midgut; it has no endodermal floor and remains temporally connected to the yolk sac by the vitelline duct (yolk stalk). Development of the primitive gut and its derivatives is often addressed as comprising four regions:

The pharyngeal gut, or pharynx, extends from the oropharyngeal membrane to the respiratory diverticulum and is part of the foregut; this section is particularly important for development of the head and neck and will be dealt with later.

The rest of the foregut which lies caudal to the pharyngeal tube and extends as far caudally as the liver outgrowth.

The midgut that begins caudal to the liver bud and extends to the junction of the right two-thirds and left third of the transverse colon in the adult.

The hindgut which extends from the left third of the transverse colon to the cloacal membrane.

The endoderm forms the epithelial lining of the digestive tract and gives rise to the parenchymal cells of glands including hepatocytes, the exocrine pancreatic acinar cells and the endocrine islet cells. The stroma or connective tissue elements of the digestive tract wall, musculature of the alimentary tract, connective tissue elements of the peritoneum are all derived from visceral mesoderm.

When the embryo is approximately 4 weeks old, the respiratory primordium (lung bud) appears at the ventral wall of the foregut at the border with the pharyngeal gut. The tracheoesophageal septum gradually partitions this diverticulum from the dorsal part of the foregut thus dividing the rostral part of the foregut into a dorsally locate esophagus and a ventrally located respiratory primordium. The oral cavity develops independent of the foregut.

The Oral Cavity

The oral cavity arises from the stomodeum, which is an invagination of ectoderm on the ventral side of the embryo's head. The stomodeum is separated from the end of the foregut by the oropharyngeal membrane. The supportive structures of the oral cavity are derived from the first branchial arch. By the end of the fourth week of embryonic development, the frontonasal, the maxillary, and the mandibular processes are visible. The face and palate complete midline fusion between the 6th and 12th week of gestation, whereas the upper lip fuses by the 6th week of gestation.

The branchial arches are structures that appear during embryonic development and serves as a building block for the face, neck, and oropharynx. They are six arches that give rise to cartilage, bone and muscles of the region. The pharyngeal arches are derived from all three germ layers (the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm). The neural crest cells enter these arches where they contribute to the formation of the skull and facial bones and cartilages. The first pharyngeal arch (the mandibular arch) gives rise to components of the jaw and muscles of mastication. During development, this first arch separates into a dorsal maxillary prominence and a ventral mandibular prominence.

The lips

The lips develop from the first pharyngeal arch in the 6th – 8th week of gestation; the upper lip develops from the maxillary process whereas the lower lip develops from the mandibular process. This region is prone to developmental anomalies such as cleft lip and cleft palate. The head ectoderm derm gives rise to the stratified epithelium covering of the lips, whereas the head mesenchyme which is of neural crest origin gives rise to the connective tissue core and musculature of the lips.

The Teeth

Teeth development is a complex process that involves the oral ectoderm and the neural crest ectomesenchyme. The ectoderm gives rise to the enamel and the gum epithelium, whereas the neural crest ectomesenchyme gives rise to the dentin, cementum, the periodontal ligament, and the alveolar bone. The tooth development passes through three stages, which are the bud stage, the cap stage, and the bell stage. The bud stage commences in the 8th week of gestation and is characterized by the emergence of the enamel organ. The cap stage is characterized by a marked growth of the enamel organ that differentiates into an inner and an outer enamel epithelium in addition to an intermediate layer called the stratum intermedium. This stages spans over the 10th week to the 14th week of gestation. The bell stage is characterized by disintegration of the dental lamina and formation of the dental hard tissues namely the dentin, enamel and cementum. In the bell stage the shape of the tooth crown is defined, and cells differentiate into ameloblasts which yield the enamel and odontoblasts that secrete the dentin.

The process continues until a fully developed tooth consisting of a crown, root, pulp, and periodontium is formed comprising and enamel, dentin, pulp, and cementum surrounded by the periodontal ligament, the gum and the bony socket.

The Palate

The palate develops by fusion of several embryonic structures, primarily derived from the first branchial arch. Its development begins in the 5th week of pregnancy when the palatal shelves develop from the maxillary prominence. During the sixth week of gestation, the palatal shelves grow vertically downwards alongside the developing tongue, move towards each other and ultimately fuse in the midline; this process is completed by the 12th week of gestation thus creating the definitive secondary palate, which separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity.

A renowned developmental anomaly of the palate is the cleft palate, which occurs when the palatal shelves fail to fuse properly, resulting in an opening that can affect the roof of the mouth and, in severe cases, the nasal cavity causing difficulties with feeding and speech. It may be accompanied by a unilateral or bilateral cleft lip.

The Tongue

Development of the tongue begins around the 4th week of gestation with the formation of the tongue primordia that from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th pharyngeal arches. The anterior two-thirds of the tongue, which is also called the oral part of the tongue, originates from the first pharyngeal arch. The medial lingual swelling (tuberculum impar) and the pair of lateral lingual swellings proliferate and merge to form this oral part of the tongue. This process of fusion of the medial and lateral primordial tongue structures is completed by the 8th week of gestation.

The posterior third of the tongue which is called the pharyngeal part of the tongue, develops from the 3rd and 4th pharyngeal arches. First, a midline swelling is formed in the 3rd pharyngeal arch and eventually covers the hypobranchial eminence, which is a structure derived from the second pharyngeal arch. This process ultimately results in the formation of the posterior third of the tongue. A groove called the sulcus terminalis demarcates it anteriorly.

The root of the tongue develops from the 4th pharyngeal arch and the neighboring regions of the 3rd arch. These primordia continue to develop and fuse, contributing to the formation of the epiglottis and the root of the tongue. The fusion of these components is completed by the 8th week of gestation.

The epithelium and the intramural glands of the tongue are ectodermal in origin, whereas the lingual connective tissue stroma and lingual musculature are mesodermal in origin, being derived from the mesenchyme of the occipital somites.

The sensory innervation of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is derived from the lingual branch of the 5th cranial nerve, trigeminal nerve. The taste innervation of this region is derived by the chorda tympani branch of the 7th cranial nerve, which is called the facial nerve. The posterior third of the tongue receives its sensory innervation from the 9th cranial nerve, which is the glossopharyngeal nerve, the root of the tongue on the other hand is innervated by the 10th cranial nerve i.e. the vagus nerve. The intramural or intrinsic lingual muscles are innervated by the 12th cranial nerve, the hypoglossal nerve.

Development of the Salivary Glands

Development of the salivary glands at about the 6th and 7th weeks of embryonic development. All major and minor intramural salivary glands originate from the stomodeal ectoderm which gives rise to the oral and lingual epithelium. The epithelium proliferates and dips into the underlying mesenchyme forming epithelial buds that eventually differentiate into secretory acini and conducting ducts of the salivary glands. Development of the major salivary glands which include the parotid, submandibular and the sublingual salivary glands will be discussed here.

The Parotid Gland

The parotid glands, which are the largest of the salivary glands, begin to develop in the 6th week of gestation. The initial stage of their development involves the formation of a pair laterally located epithelial buds in the region of the future cheeks. These buds proliferate and grow dorsally into the surrounding mesenchyme. The buds undergo repeated branching to form a network of solid cylindrical ducts. The ducts then begin to canalize in the 10th week of gestation, thus forming the duct system of the parotid salivary gland. The terminal blind-ended parts of these ducts proliferate, enlarge and then differentiate into secretory units known as acini which start to synthesize and produce a watery secretion.

Submandibular Gland

The submandibular glands begin to develop as a pair of buds shortly after the appearance of parotid gland buds, at about the 7th week of gestation. These epithelial buds which are located in the floor of the mouth, on either side of the developing tongue, proliferate and extend into the underlying mesenchyme. By the 12th week of gestation, the ductal system of the submandibular gland originating from the epithelial buds elongate and branch. The terminal ends of each ductal branch proliferates and enlarges foreshadowing formation of the glandular acini, which are mixed seromucous acini containing a mixture of serous secreting cells and mucus secreting cells. The serous cells are predominant at birth, but the mucous cells increase in number and predominate postnatally.

Sublingual Gland

The sublingual gland is the last of the major salivary glands to develop; its primordium first appears in the 8th week of gestation. The development process is similar to that of the parotid and submandibular glands, originating from epithelial buds surrounding the sublingual folds on the floor of the mouth beneath the developing tongue. The epithelial buds develop into cords, which canalize forming the sublingual ducts. The terminal parts of each ductal branch enlarges into a spherical mass that foreshadows the formation of a secretory acinus. The acini are primarily made of mucus secreting cells. To begin with, the sublingual gland develops lateral to the submandibular gland but later in development it acquires a position anterior and superior to the submandibular gland.

Developmental anomalies of the salivary glands include aplasia and the presence of ectopic salivary gland tissue. Aplasia causes variable degrees of xerostomia (dry mouth or oral dryness), whereas ectopic salivary gland tissue may occur as accessory salivary gland tissue, which could be associated with branchial cleft anomalies. Salivary ducts anomalies include congenital atresia which results from failure of canalization that causes salivary retention.

The Primitive Pharynx

The cranial part of the foregut enlarges and develops into the primitive pharynx; thus, the primitive pharynx is lined by endoderm. It shows pairs of lateral outpocketings known the pharyngeal pouches that are associated with ectodermal pharyngeal arches with mesenchyme in between. The pharyngeal pouches constitute developmental primordia for a number of important structures and organs which include the middle ear ling, eustachian tube, the palatine tonsils, the thyroid, the parathyroids and the thymus. They are six pairs of pouches, but the 4th, 4th, and 6th pouches fuse together leaving four pairs of pouches to play important roles in the embryonic development of this region.

After formation of the derivatives of the pouches (middle ear, thymus, palatine tonsils, thyroid glands, parathyroids and the thymus), what is left of the primitive pharynx constitutes the definitive pharynx. Accordingly, all these glands and structures are of endodermal origin since the primitive pharynx and its pouches develop from the foregut which is of endodermal origin. The definitive pharynx has three parts, which are the nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx. The developing oral cavity is not part of the definitive pharynx and remains separated from it by the oropharyngeal membrane or septum. The oropharyngeal membrane which is also called the buccopharyngeal septum consists of endoderm facing the pharynx and ectoderm facing the oral cavity along with the mesenchyme sandwiched between the two. In the 4th week of embryonic development, the oropharyngeal membrane begins to break down and ultimately disappears thus establishing confluence of the oral cavity and the pharynx. Persistent oropharyngeal membrane and atresia of the oropharyngeal membrane are congenital anomalies. Persistence of the buccopharyngeal membrane can lead to orofacial defects and is always associated with cleft palate and with difficulty of respiration requiring emergent surgical intervention. The epithelium of the oropharynx is of endodermal origin whereas the connective tissue elements and musculature of the pharyngeal wall are of mesoderm origin.

Development of The Esophagus

The esophagus develops from that part of the foregut that lies immediately behind the pharynx. Its development is stimulated signaling molecules which include BMB and SOX2. It begin to develop in this anterior part of the foregut in about the 4th weeks of embryonic development concurrent with the appearance of the respiratory diverticulum or lung bud from the ventral wall of the foregut at the border with the pharyngeal gut; to begin with the esophagus and the trachea share a common lumen in the anterior (cranial) parts of the foregut. A tracheoesophageal septum appears and gradually partitions the ventrally located respiratory diverticulum from the dorsally located esophagus. The esophagus attains a short tubular structure that rapidly elongates with the elongation and descent of the lung.

The epithelium of the esophagus, which is stratified squamous epithelium originates from the endoderm whereas the connective tissue element of the lamina propria and submucosa as well as the esophageal musculature, both smooth and straited, are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm.

A renowned development anomaly of the esophagus is esophageal atresia where the esophagus has two separate sections—upper and lower—that do not connect, thus making it impossible for the food to pass food from the mouth to the stomach. Esophageal atresia often accompanies another anomaly called the tracheoesophageal fistula which is an abnormal connection between the esophagus and trachea resulting from improper separation of the trachea from the foregut.

Development of The Stomach

The stomach develops from the distal part of the foregut just caudal (inferior) to the caudal end of the esophagus and is thus of endodermal origin. It has a dorsal and a ventral mesocardium. The foregut and other parts of the gut are suspended dorsal and ventral body walls by mesenteries which are double layers of the peritoneum. Some of the abdominal organs such as the stomach are enclosed by the peritoneum and are called intraperitoneal; other are not completely enclosed but partially covered by the peritoneum are referred to as retroperitoneal organs e.g. the kidneys. The mesenteries extending between two organs are called peritoneal ligaments. The mesenteries and the peritoneal ligaments conduct blood vessels and nerves to the abdominal organs.

The primordium of the stomach appears in the 4th week of gestation as a small dilation of the distal foregut. Its shape, size and location change greatly as the embryonic development proceeds. The stomach rotates 90o clockwise around its longitudinal axis, resulting in its right side facing posteriorly and its left side facing anteriorly. This is why the left vagus nerve innervates the anterior wall, whereas the right vagus nerve innervates the posterior wall, Concurrent with this rotation, the gastric primordial cells proliferate more rapidly in the posterior wall of the stomach than in the anterior wall, resulting in the formation of the greater and lesser curvatures. Moreover, the stomach rotates around its antero-posterior axis, resulting in the caudal end (pyloric region) moving upward and to the right and its cranial end (cardiac region) slightly downward and to the left. As a result, the stomach assumes its final position, with its pylorus located superiorly to the left and its cardia located inferiorly to the right. The rotational changes of the stomach also alter the position of the mesenteries. It is to be recalled here that the stomach is attached to the dorsal and ventral abdominal walls by the dorsal mesogastrium and the ventral mesentery. The rotation of the stomach around the longitudinal axis pulls the dorsal mesogastrium to the left and the ventral mesogastrium to the right; this creates a space behind the stomach known as the omental.

The endoderm of the foregut gives rise to the surface epithelium of the stomach which is a simple columnar epithelium made of mucus secreting cells. It also gives rise to cardiac, fundic and pyloric glands of the stomach which contain different types of secretory cells which include HCl-secreting parietal cells, pepsinogen-secreting chief cells, and peptide hormone-secreting enteroendocrine cells. The connective tissue elements of the lamina propria and submucosa along with the smooth muscle fibers of the gastric wall are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm.

Development of the Duodenum

The duodenum develops from two primordia in the 4th week of gestation; a cranial primordium that originates from the caudal part of the foregut and a cranial primordium that originates from the midgut; the junction between the primordia lies just distal to the origin of the bile duct. The developing duodenum forms a C-shaped loop that initially projects ventrally. Along with the rotation of the stomach, the duodenum also rotates to the right and becomes pressed against the posterior abdominal wall, thus becoming retroperitoneal. Due to its dual origin, the duodenum has dual blood supply from branches of the celiac trunk and other branches from the superior mesenteric artery.

Development of the Liver and Gall Bladder

The development of the liver begins in the 4th week of gestation, with the appearance of the liver bud, which is an evagination of the endoderm of the ventral wall of distal foregut; the live bud is also known as the hepatic diverticulum. The distal end of the hepatic diverticulum proliferates and undergoes repeated branching and rebranching giving rise to the hepatic cords. The endodermal cells differentiate into hepatocytes which are highly specialized multifunctional cells. Cellular proliferation that occurs much rapidly on one side results in the formation of a larger right lobe and a smaller left lobe. Further development and segmentation of the liver is determined by the flow of oxygenated blood reaching it from the umbilical vein. The hepatic cords are invaded with wide lumen capillaries forming the liver sinusoids.

The stalk connecting the liver bud with the foregut becomes narrower and narrower forming the bile duct. A ventral outgrowth from the bile duct proliferates and enlarges forming a hollow structure which is the gallbladder. The endoderm of this outgrowth differentiates into the simple columnar epithelium of the gall bladder, whereas the connective tissue elements and musculature of the cystic wall are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm. The bile duct originates from the anterior aspect of the duodenum but due to the rotation of the duodenum along with rotation of the stomach, the bile duct ultimately drains into the posterior aspect of the duodenum.

The connective tissue elements of the liver including Glisson capsule, the intralobular septa and the intralobular stroma are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm. During early development the liver, the hepatic diverticulum extends into ventral mesentery foreshadowing the future positions the definitive liver between the foregut and ventral abdominal wall, thus dividing the ventral mesentery into the lesser momentum and the falciform ligament. The liver develops and enlarges greatly, ultimately occupying a large portion of the upper abdominal cavity. The mesoderm surrounding the liver surface differentiates into the visceral peritoneum except on its cranial surface, which lies in direct contact with the septum transversum of the diaphragm. This surface remains in contact with the diaphragm and is never covered with the visceral peritoneum and is thus referred to as the bare area of the liver.

Development The Pancreas

The pancreas has a dual origin; it develops from two separate pancreatic buds, a dorsal bud and a ventral bud that later join to form a single organ. The dorsal pancreatic bud forms as a direct outgrowth of the dorsal wall of the duodenum, whereas the ventral bud forms as an outgrowth of the bile duct. When the duodenum rotates, it pulls the ventral pancreatic bud dorsally and inferior to the ventral pancreatic bud. Subsequently, the pancreatic buds along with their rudimentary duct systems fuse to give rise to the pancreas. The ventral pancreatic bud forms the uncinate process and the inferior part of the head of the pancreas. The dorsal pancreatic bud forms the superior part of the head, the neck, and the body of the pancreas. The distal part of the dorsal pancreatic duct and the entire ventral pancreatic duct form the main pancreatic duct of Wirsung.

Both the dorsal and ventral pancreatic primordia from ducts the branch and rebranch in a fashion similar to that developing salivary gland. The terminal ends of the ducts enlarge and differentiate into secretory cells. Most of these secretory cells remain attached to the ducts forming the pancreatic acini which secrete digestive enzymes. A smaller proportion of these secretory cells detach from the ducts and transform into hormone secreting endocrine cells that produce glucagon (α cell), insulin (β cells), and somatostatin (δ cells). These endocrine cells aggregate into small groups known as the pancreatic islets of Langerhans. The connective tissue elements of the pancreatic capsule and stroma are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm.

The Midgut

The midgut is the middle segment of the primitive gut that lies between the foregut and the hind gut. It is made of endoderm but unlike the foregut and the hindgut it has no floor of its own; it gives rise to several parts of the alimentary tract including the distal half of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the cecum, the appendix, the ascending colon, the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. Derivatives of the midgut are supplied by the superior mesenteric artery. These organs and parts of organs develop at the expense of midgut, ultimately the midgut becomes narrow floorless tube that is connected ventrally to the yolk stalk.

In the 5th week of gestation, the midgut undergoes a rapid elongation that surpasses the pace by which the abdominal cavity enlarges; this forces the intestines derived from the midgut to bend forming of the primary intestinal loop. The apex of this primary loop remains patent communicating with the yolk sac via the yolk stalk. The superior (cranial) limb of the loop develops into the inferior half of the duodenum, the jejunum, and superior half of the ileum, whereas inferior (caudal) limb of the loop develops into the distal half of the ileum, the cecum, the ascending colon, and the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. By continuing elongation of derivatives of the midgut along with concurrent enlargement of the abdominal organs, the primary intestinal loop is forced to protrude into the umbilicus by a process called physiological herniation. Concomitantly, the intestinal loop rotates counterclockwise around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery, pushing the cranial limb caudally and towards the right side, and pushing the caudal limb cranially and to the left. Further elongation of the jejunum and ileum develop results in a series of folds called the jejunoileal loops. In the 10th week, the herniated midgut retracts into the abdomen. As a result, the cecum, which was placed under the liver, is pushed caudally. By the 11th week, the intestines are completely retracted into the abdomen. The jejunum, ileum, cecum, the transverse colon, and sigmoid colon remain suspended by a short mesentery from the dorsal body wall, thus becoming intraperitoneal.

Hindgut

The hindgut is distalmost part of the primitive gut; it gives rise to the distal third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and the upper 2/3rd of the anal canal. In the early stages of embryonic development, the hindgut along with the posterior portion of the cloaca contributes to the formation of the anorectal canal whereas the allantois along with the hindgut participates in the formation of the urogenital sinus. The cloaca is separated from the exterior of the body by the cloacal membrane which is lined by endoderm to the inside and by the ectoderm to the outside. In the 7th week of gestation, a layer of mesoderm grows between the allantois and the hindgut forming the urorectal septum, which divides the cloaca into the urogenital sinus and the anorectal canal. The urogenital sinus forms the future bladder, parts of the urethra, and the phallus, whereas the anorectal canal develops into the rectum and most of the anal canal. Thus, whereas the upper 2/3rd of the anorectal canal is derived from the endoderm of the hindgut, the lower 1/3rd of this canal is derived from the surface ectoderm of the cloaca. Rupture of the cloacal membrane in the 7th week of gestation marks the establishment of an exit from the alimentary tract and connects the upper and lower parts of the anorectal canal; the location of this juncture is demarcated by the pectinate line, which is an irregular folding of the alimentary mucosa, where the epithelial lining of the canal changes from a simple columnar epithelium to a stratified squamous epithelium.

The anorectal canal is of dual origin, its upper 2/3rd which lies superior to the pectinate line is derived from the hindgut is supplied by the superior rectal arteries, which are branches of the inferior mesenteric artery. The lower 1/3rd of the anorectal canal which lies inferior to the pectinate line is supplied by the inferior rectal arteries, which are branches of the internal pudendal arteries.

Wall Plan of the Intestines

The lining epithelium of the intestinal tract and the epithelium of its mucosal glands and submucosal glands is of endodermal origin. The connective tissue elements of the intestinal lamina propria and submucosa are derived from the splanchnic mesoderm. Likewise, the smooth muscle fibers of wall are derived from splanchnic mesoderm. The endoderm differentiate into several functional cells that include the highly absorptive enterocytes, the mucus-secreting goblet cells and the lysozyme-secreting Paneth cells. The epithelium of the small intestine forms finger-like projections called villi which increase the surface area and efficiency of absorption of nutrients; the large intestine is devoid of such villi.

Comments