Urogenital Development

- teachanatomy

- Jul 4, 2025

- 23 min read

The urinary system, the genital system and the female genital system have a common developmental primordium and common early developmental structures and accordingly are collectively referred to as the urogenital system or the genitourinary system. Its developments comprises development of the urinary system, which includes the kidneys, ureter, and bladder, and development of the male genital system (reproductive system), which includes the testes, epididymis, vas deferens, male sex glands, male accessory sex glands, and the penis, or development of the female genital (reproductive) system which includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and the female external genitalia. The system develops the urogenital ridge, which is a bilateral mesodermal structure. The urogenital ridge, which is the precursor of the kidneys and the gonads, is a thickened area of mesoderm on either side of the aorta. The urogenital ridge is the developmental primordium of both the urinary system and the genital systems; it gives rise to the gonadal ridge and the mesonephros. The gonadal ridge will differentiate into the gonad, whereas the mesonephros gives rise to the urinary system and components of the internal reproductive tract. The primordial germ cells originate in the yolk sac outside the embryonic body and migrate into embryonic body to inhabit the right and gonadal ridges. In genetically male individuals with XY sex chromosome complement, the gonadal ridge develops into a testis; in genetically female individuals with XX sex chromosome complement, the gonadal ridge develops into an ovary.

Development of the Kidneys

The kidneys develop from the nephrogenic plate of the intermediate mesoderm in three forms that appear in a chronological, craniocaudal sequence; the first and most cranial of these is the pronephros stage, intermediate one is the mesonephros, and the last and most caudal is the metanephros. The pronephros, the mesonephros, and the metanephros are sets of mesodermal tubular structures.

The pronephros represents the earliest stage in the development of the urinary system. It develops in the cranial most region of the nephrogenic plate towards the end of the 3rd week of embryonic development; it is quite transient and nonfunctional in humans. In the earliest stages of its development, the pronephros appears as solid cell groups that form vestigial excretory units known as the nephrotomes. In the 4th week the pronephros regress and by the end of the week it disappears altogether.

The mesonephros is also transient in humans. It is also a paired structure that develops in the thoracic and lumbar regions the nephrogenic plate; each mesonephros consists of a duct that extends in a craniocaudal direction along with a set of parallel tubules that extend lateral from the duct. The duct is known as the mesonephric duct and the tubules are known as the mesonephric tubules. The mesonephros is a functional structure that appears in the 4th weeks of embryonic development at a time when the pronephros is regressing. It continues to be the functioning kidney of the developing embryo until the 12th week of gestation. The mesonephric tubules elongate and bend into S-shaped structures. The lateral ends of the mesonephric tubules expand and a acquire tufts of capillaries that forma the first glomeruli. The distended end of each tubule invaginates and form a cup shaped structure known as Bowman’s capsule that engulfs the glomerulus forming together a renal corpuscle. All mesonephric tubules connect medially with the mesonephric duct and drain into it. The mesonephric duct is also known as the Wolffian duct.

The mesonephros continues to grow and by the 7th week it forms a large ovoid structure on each side of the midline adjacent to the developing gonad; together the developing mesonephros and the developing gonad constitute a ridge known as the urogenital ridge. In the 8th week the cranial mesonephric tubules start to degenerate and disappear. This degeneration process continues caudally and by the time the metanephros develops the mesonephros has disappears. Nonetheless, in genetically male embryos (with an XY sex chromosome complement) a few of the caudal mesonephric tubules persist and contribute to the formation of parts of the male genital system.

The metanephros is the definitive kidney and is the third and last of the urinary primordial structures to envelop. It begins to appear in the 5th week of embryonic development whilst the mesonephros is still functioning and is fully and functional the 12th week of embryonic development. The metanephros serves as the primary excretory organ of the developing embryo and develops into the mature kidney after birth. The metanephros has a dual embryonic origin partly developing from the and partly developing from the metanephrogenic tissue or the metanephric blastema. The ureteric bud develops as an outgrowth of the distal portion of the mesonephric duct (the Wolffian duct) close to its entrance into the cloaca. The bud grows laterally and its distal end becomes distended and pushes ahead of it a condensation of mesodermal cells that forms the metanephric blastema or the metanephrogenic tissue. The renal ducts develop from the metanephric bud, whereas the renal tubules develop from the metanephric blastema.

The ureteric bud, which is also known as the ureteric diverticulum, arises as an evagination of the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct. The distal part of the bud dilates and forms the primitive renal pelvis and bifurcates into two parts which develop into the major calyces of the kidney. The major calyces in turn give rise to secondary buds; the secondary buds form minor calyces of the kidney where from branching tubular structures arise forming the collecting ducts and collecting tubules of the kidney. The proximal nondilated part of the original ureteric bud develops into the ureter.

The metanephric blastema (metanephrogenic tissue) is molded over the distal end of the ureteric bud as a cap. By continuous development of the distal end of the ureteric bud and its repeated branching to form the renal collecting ducts and tubules, the metanephric blastema is pushed forming a cap around the distal end of each collecting tubule. The collecting tubules induce the metanephric blastema caps to differentiate into tubular structures, known as the nephrons. One end of the tubular nephrons unite the distal end of a collecting tubule whereas the other end of the nephron is approached by a network of capillaries. This end of the nephron enlarges and forms a cup-shaped structured called Bowman’s capsule. The capsule surrounds the capillary network (now known as the glomerulus) and together form the renal corpuscle. The fetal blood is filtered of its content of waste material by the renal corpuscle. The nephrons increase in length, bend, and twist forming the proximal tubule, the loop of Henle and distal tubule.

The renal interstitium, septa and the renal capsule develop by differentiation of the mesenchyme in between and around the developing parts of the ureteric 1bud and ureteric blastema. For development of the renal collecting ducts and tubules of the nephron, the mesodermal cells of the ureteric bud and the ureteric blastema develop into simple columnar, simple cuboidal or simple squamous epithelium. For development of the renal stroma the mesodermal cells differentiate into fibroblasts that produce the connective tissue elements of the renal interstitial and renal capsule.

The ureter develops from proximal the nondistended part of the ureteric bud which differentiates into transitional epithelium (urothelium) of the ureter. The connective tissue elements and the smooth muscle fibers of the wall of the ureter develop from the surrounding mesenchyme.

Urinary Bladder and the Urethra

The urinary bladder and the urethra have an endodermal origin; the develop from the cloaca, which is a dilatation of the caudal end of the hindgut. In the 4th week of embryonic development, the cloaca divides into an anterior chamber called the urogenital sinus and a posterior chamber called the primitive anal canal; the urorectal septum separates between the two. The upper part of the urogenital sinus develops into urinary bladder which is continuous with allantois. The connecting segment between the two becomes narrow and forms the arachis that remains connecting the urinary bladder with the umbilicus. Postnatally, the urachus obliterates and median umbilical ligament. The lower part of the urogenital sinus is narrower than the upper part gives rise to the entire urethra in females and the prostatic and membranous urethrae in males. The cloacal endoderm differentiates into the transitional epithelium of the bladder and urethra, whereas the connective tissue and muscle fibers of the walls of the bladder and the urethra are derived from the surrounding mesenchyme.

To begin with, the bladder which develops from the cloaca and the ureters which develop from the Wolffian ducts are widely separated. Nonetheless, expansion of the cloaca and enlargement of the urinary bladder bring the bladder and the ureters in contact with each other and ultimately the ends of the ureters are absorbed within bladder.

Congenital Anomalies of the Urinary System

The most common anomalies of the urinary system are the anomalies of the kidneys. They could be mild without noticeable problems or severe that require medical attention. They include renal agenesis, polycystic kidney, and renal dysplasia. Renal agenesis means absence of one or both kidneys. Unilateral renal agenesis is the failure of development of one of the two kidney. In this case, the existing kidney shoulders the responsibility of both kidneys normally without problems. Bilateral renal agenesis on the other hand is a fatal condition. It causes lack of the amniotic fluid and failure of the lungs to develop normally, and accordingly the newborn dies shortly after birth to respiratory failure. Polycystic kidney is a renowned kidney birth defect wherein the kidney contains numerous fluid-filled cysts. The defect arises due to genetic mutation that affect the PKD genes which control the production polycystic proteins causing malfunctioning of the primary cilia of the kidney tubules. The primary cilia are sensory cilia present on the luminal surface of renal tubular epithelial cells, that detect extracellular signals in the tubular lumen thus influencing flow and reabsorption of electrolyte. Malfunction of these cilia result in excessive cell growth and fluid production leading to the formation of fluid-filled cysts. The progressive development of cysts may lead to kidney failure.

Renal dysplasia is a congenital kidney disease that results abnormal differentiation of cells of the developing kidney. Dysplastic kidneys are smaller than normal kidneys and contain cysts and abnormal renal tissues. This causes impairment of the renal functions, which may require medical intervention.

Development of the Genital System

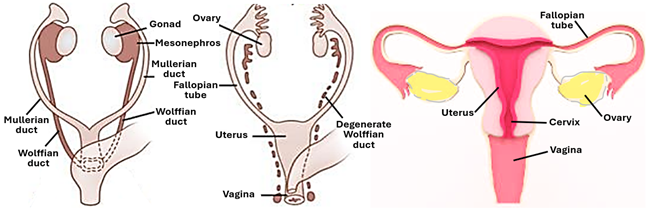

The male and female genital system develop from the same primordial structures which are difficult to differentiate, and according, the early stages in the development of the male and female genital systems are referred to as the indifferent stages, where it is impossible differentiate between a male embryo and a female embryo on the basis of the appearance of the developing genital structures. Depending on the type of sex chromosomes, the primordial genital structures develop into either male genital organs or female genital organs. In both males and females, the genital system develops from primordial gonads and two sets of tubular structures known as the Wolffian ducts (mesonephric ducts) and the Mullerian ducts (paramesonephric ducts).

Development of the Male Genital System

The first indication for the embryonic development of the gonads is the formation of the gonadal ridge, which has identical features in both male and female embryos. There is a pair of ridges, one on either side of the body. The ridges differentiate into testes in male embryos influenced by the SRY (sex-determining region on Y) gene of the Y chromosome; in female embryos, in absence of the Y chromosomes and its SRY gene, the gonadial ridges differentiate into ovaries. It is to be recalled that genetic sex determination takes place at the time fertilization depending on whether the fertilizing sperm bears an X or a Y sex chromosome. It is the Y chromosome that determines the differentiation pathway of the gonadial ridge. In the early stages of the embryonic development, it is not possible to tell whether the gonadial ridge is developing into a testis or into an ovary; the developing gonad at this stage is referred to as the indifferent gonad.

In the early stages of gonadal development, primordial germ cells migrate from the splanchnopleure of the yolk sac along the allantoic stalk to the gonadal ridges. Concurrently, supporting cells of the gonadal parenchyma differentiate from the coelomic epithelium and gonadal mesenchyme. The gonadal ridge is bipotential; it can develop into either a testis or an ovary. Several factors are involved in early development of the gonads; they include sine oculis homeobox (SIX), paired box gene (PAX), neuregulin (NRG), and homeobox gene 9 (LHX9). In the 7th week of embryonic development, the SRY gene of the Y chromosome begins to express itself, determines the direction of the gonadal development by triggering the development of the testis. In the absence of such a trigger, the indifferent gonad develops into an ovary. In the developing testis the gonadal medulla develops into the seminiferous tubules and the gonadal cortex degenerates. The opposite occurs in females where the ovarian follicles develop in the gonadal cortex, leaving the medulla devoid of ovarian follicles.

In the presence of activated SRY gene of the Y chromosome the indifferent gonad takes a developmental pathway that leads to the formation of the testis. Primordial sex cells which migrated from the extraembryonic yolk sac splanchnopleure differentiate into spermatogonia, the mother cells of sperms. Concurrently, mesenchymal cells of the developing gonad differentiate into Sertoli cells and Leydig cells. The seminiferous tubules develop from the primitive sex cords that develop from the epithelium covering the gonadal ridge (the germinal epithelium). Cells of the germinal epithelium proliferate and dip into the mesenchyme forming irregular cords known as the primitive sex cords. At this stage it is still impossible to differentiate between a developing testis and a developing ovary as both have primitive cords connected to the surface epithelium; therefore, the gonad is still an indifferent gonad. In males the primitive and penetrate deep into the core of the gonads forming the medullary cords. These cords are infiltrated by primitive germ cells and Sertoli cells thus transforming into seminiferous tubules. They are solid tubules that lack lumina and remain solid cords until puberty when they become hollow tubules. By the 8th week of embryonic development Ledig cells begin to synthesize and secrete testosterone which initiates the development of the genital tract and the penis. Towards the hilum of the developing testis the sex cords join a network of passages that form the rete testis. The ductuli efferences which join the rete testis with epididymis formed by remnants of the mesonephric tubules in the region.

In the 6th and 7th week of embryonic development the medullary testicular cords are formed of Sertoli cells and spermatogonia. The mesenchyme in between the cords differentiates into the testicular interstitium. Some of the mesenchymal cells differentiate into testosterone producing interstitial cells known as Leydig cells. Some of the mesenchymal cells that immediately surround the developing seminiferous tubules, differentiate into peritubular myoid cells, which are capable of contraction like muscle cells. in the 5th week of embryonic development, the mesenchyme surrounding the developing testis differentiates into a tough fibrous connective tissue capsule called the tunica albuginea. Septa emerge from the tunica albuginea dividing the testis into lobules.

The Epididymis and the Vas Deferens

The epididymis develops from the caudal parts of the mesonephros. Under the influence of androgens, the mesonephric (Wolffian) tubules and the caudal portion of Wolffian duct, into which they drain, fuse together and form the primordial epididymis, which elongates, undergoes folding and coiling to become the definitive epididymis. The cranial parts of Wolffian duct usually degenerates but may persist forming what is known as the appendix of the epididymis. The epithelium of the epididymis develops from the lining of the Wolffian duct and tubules whereas the connective tissue elements and the smooth muscle fibers of the epididymal wall develop the regional mesenchyme.

Both the vas deferens and the seminal vesicle develop from caudal part of the mesonephric duct (Wolffian duct). The epithelium of the vas deferens (ductus deferens) and the parenchyma of the seminal vesicle develop from the epithelium of the mesonephric duct, which is mesodermal in origin. The stromal elements and the smooth muscle fibers in both structures develop from the surrounding mesenchyme under the influence of testosterone. In case of the vas deferens there is great proliferation of smooth muscle fibers that result in a very thick-walled muscular tube. The primordium of the seminal vesicle appears in the 10th week of embryonic development as evaginations of the distal end of the mesonephric duct. The evagination (the bud) elongates, branches and rebranches forming ducts of the gland; the distal blind-ended terminals enlarge to form the secretory units of the gland. The very distal end of the mesonephric duct forms the ejaculatory which traverses the prostate to open into the urethra. The prostate originates from the prostatic utricle of the urogenital sinus, so it is of endodermal origin different from the seminal vesicle which is mesoderm.

In the 10th week of embryonic development, a solid epithelial bud called the utricle of the prostate, originates from the developing urethra (that develops from the urogenital sinus). The epithelial bud elongates, branches and rebranches forming ducts of the prostate gland; the distal ends of the ducts distend and differentiate into the prostatic acini. The prostatic stroma and smooth muscle develop from the regional mesenchyme.

Testicular Descent

The first stage of testicular descent, which is called the transabdominal phase occurs in the 8th week of embryonic development. It comprises the movement of the testes from their starting position on the posterior abdominal wall adjacent to the kidney down towards the internal inguinal ring, orchestrated by non-androgenic hormones. The gubernaculum is a ligament-like structure that develops from the peritesticular mesenchyme concomitant with the development of the testis. It plays a significant in the process of testicular descent. The gubernaculum enlarges leading to the formation of the gubernacular bulb. At the same time, the cranial suspensory ligament regresses. Regression of the cranial suspensory ligament facilitates the testicular descent. The gubernaculum contracts and shortens, and as it shortens it pulls the testes towards the inguinal region. The intraabdominal phase of testicular descent is followed the inguinal phase, which begins in the 26th week of embryonic development. The inguinal phase is androgen-dependent and involves the passage of the testes from the internal inguinal ring down into the scrotum. It has specific pre-requisites which include the formation of a peritoneal outpouching known as the processus vaginalis, dilation of the inguinal canal by the distal portion of the gubernaculum (the gubernacular bulb), and abdominal pressure to push the testes through the inguinal canal. After completion of the testicular descent, the gubernaculum regresses, leaving behind a remnant testo-scrotal attachment. Usually, the testis completes its descent to settle within the scrotum by the 33rd week of gestation.

Developmental Anomalies of the Male Genital System

Congenital anomalies of the male genital system can affect the testes, the epididymis, the sex glands, and the external genitalia. Examples of developmental anomalies of the system include cryptorchidism, anorchia, hypospadias, and testicular torsion. All these anomalies tend to have negative impacts on fertility and sexual function.

Cryptorchidism is the absence of one or both testis in the scrotum; it results from failure of the testis to descend during the prenatal period from the abdomen into the scrotal sac. In over 95% of the new porn males, the testes are present within the scrotal sac before birth. In most of the remainders testicular descent is completed with the three months of postnatal life. In about 1% of infants there is cryptorchidism after the age of three months. At puberty the undescended testis fails to produce sperms and cause infertility. In the first year of postnatal life, and after testicular descent the inguinal canal obliterates and closes off the scrotal sac; failure of canal obliteration leaves the scrotal sac communicating freely with abdominal cavity predisposing for inguinal hernia and hydrocoele of the testis.

Anorchia is the complete failure of one or both testes to develop due to failure of development of the gonadal ridge or failure of differentiation of the gonadal ridge. Anorchia affecting both testis is a quite a rare condition that may affect male individuals with a 46, XY karyotype.

Hypospadias is a developmental anomaly that affects the urethra. It results from incomplete fusion of the urethra folds causing an abnormal opening of the urethra along the inferior aspect of the penis. When the opening is along the dorsum of the penis the condition is called epispadias.

Development of the Female Genital System

Development of the female genital system comprises the development of the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, the uterus vagina, and the external genitalia.

Development of the ovaries

The early stages of embryonic development of the ovary is the same as those of testis till the stage of the indifferent gonad. Development of the ovary begins with differentiation of gonadal ridge in the intermediate mesoderm in the 5th week of embryonic development. The ridge shows up as a protrusion on the ventromedial aspect of the mesonephros. It is a bipotential structure capable of developing into either an ovary or a testis, and is made up of primordial germ cells and somatic cells. The primordial germ cells originate extra-embryonically in the splanchnopleure of the yolk sac. The somatic cells are mesodermal gonadal ridge cells will differentiate into stromal cells and either granulosa cells (in females) or Sertoli cells (in males). The stromal cells are mesenchymal in nature, whereas the granulosa cells and Sertoli cells are epithelial in nature. The primordial germ cells develop in the very early stage of embryonic development and can be identified in human in the endoderm of the yolk sac as early as the 5th day of embryonic development. In the 4th week of embryonic development, the primordial germ cells migrate by amoeboid movement the dorsal and caudal parts the yolk sac towards the gonadal ridge. During their migration they proliferate so that more primordial germ cells are present in the gonadal ridge than those which were originally present in the yolk sac. The arrival of the primordial sex cells to the gonadal ridge induces the formation of the primary (primitive) sex cords.

The gonadal ridge differentiates into an indifferent gonad, which is also a bipotential structure that develops into either a female gonad (ovary) or a male gonad (testis). The indifferent gonad, similar to the gonadal ridge, contains primitive (primordial) sex cords, primordial germ cells and somatic cells. The somatic cells are of two types, the granulosa/Sertoli cells and stromal cells. The primordial germ cells are present in small groups; each group being surrounded by the somatic cells. The indifferent gonad differs from the gonadal ridge in shape being spherical or ovoid instead of ridge shaped. The indifferent gonad of male embryos is not distinguishable morphologically from that of the female. In both the male and female, it consists of an outer surface cuboidal epithelium covering a central core of somatic cell cords. The primordial germ cells are confined mostly to the outer or peripheral parts of the indifferent gonad (the cortex). They were large in size, spherical in shape, with large vesicular nuclei, and faintly stained vacuolated cytoplasm. The epithelial cell cords appear as if they are invaginations of surface epithelium.

The primitive sex cords first appear in the gonadial ridge in the 8th week of embryonic development under the influence of the primordial germ cells. The medulla of the gonadal ridge and the indifferent gonad contains primitive sex cords with a few primordial germ cells. the cortex on the other hand contains more primordial sex cells. the primitive sex cords which are also known as the medullary cords degenerate and new set of sex cords called the secondary sex cords or the cortical sex cords develop; these cords contain primordial germ cells. The secondary sex cords dissociate and the component cells surround groups of germ cells known as cell nests. Later the each of the sex cell becomes surrounded by its own somatic granulosa cells thus forming primoradial follicles confined to the ovarian cortex. Meanwhile, the primordial sex cells develop into primary oocytes which enter into their first meiotic division which is arrested at it prophase.

The early-stage ovary continues to develop and gradually assumes the characteristic features of the prepubertal ovary characterized by

At puberty and in each month thereafter a group of the primordial follicles are recruited under the influence of the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and the luteinizing hormone (LH) to develop, reach maturity and ovulate. The follicular cells enlarge and proliferate forming primary follicles, fluid-filled spaces appear between the follicular cells forming tertiary follicle and the spaces coalesce into a single antrum forming mature Graafian follicle. The primary oocyte completes its meiotic division and become a secondary oocyte which is released out of the ovary by rupture of the Graafian follicle. Remnants of the Graafian follicle transform into a corpus luteum.

Development the Uterus and Fallopian tubes

The uterus and the Fallopian tubes tube are both mesodermal in origin; they develop from the Mullerian duct a pair of tubular structures that run parallel to the mesonephric ducts and are accordingly known as the paramesonephric ducts. Similar to the mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts, the paramesonephric (Mullerian) ducts originate in the intermediate mesoderm during the early stages of embryonic development.

Until the 5th week of embryonic development, the genital system remains indifferent being impossible to differentiate between males and females on the bases of the morphology of the internal genital organs. Both male and female embryos at this early age have a pair of indifferent gonads, a pair of mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts and associated tubules, and a pair of paramesonephric (Mullerian) ducts. Thereafter on the 6th week of embryonic development, and in the absence of the SRY Genene, and lack of anti-Mullerian hormone, the Wolffian ducts regress and the Mullerian ducts differentiate and grow developing into the fallopian tubes, the uterus, the cervix, and the upper part of the vagina. The Mullerian (paramesonephric) ducts grow caudally and open into the urogenital sinus. In the 6th week of embryonic development, the terminal ends of the two Müllerian ducts fuse with each other forming the uterovaginal duct, which develops into the fornix of the vagina. During further development, fusion of the two Mullerian ducts proceeds cranially but their cranial potions remain unfused and develop into the right and left Fallopian tubes. The cranial tip of each duct remains opens, expands, and assumes a funnel-shaped structure that forms the infundibulum of the fallopian tube and its fimbria. Fusion of the two Mullerian ducts to form the uterus takes place in the 10th week of embryonic development and is apparently induced by the BCL2 gene. The distal end of the uterovaginal duct contacts the posterior wall of the urogenital sinus resulting in the appearance of the Müllerian tubercle. The broad ligament of the uterus is formed by an extension of peritoneal folds and connects the pelvic walls to the fused Müllerian ducts. The hymen is formed by the urogenital sinus and the Müllerian duct. By the end of the 1/3rd trimester, the development of fallopian tubes and the uterus is complete.

The epithelium of the Fallopian tubes, the endometrial epithelium, the uterine glands, the cervical epithelium and the epithelium of the upper 1/3rd of the vagina are derived from the mesodermal Mullerian ducts. The connective tissue elements and the smooth muscle fibers of the wall of the Fallopian tubes, the endometrium, the myometrium, the perimetrium and the cervix differentiate from the surrounding mesenchyme.

Anomalies of Female Reproductive Tract

Anomalies of the female reproductive tract arise from abnormal development of the Mullerian ducts and affect the Fallopian tubes, the uterus, cervix and vagina; they include uterus didelphys, bicornuate uterus, and septate uterus. Uterus didelphys is characterized by two completely separate uteri, each with its own cervix, and separate vaginas occasionally. In the bicornuate uterus, the uterus is heart-shaped due to the presence of a deep indentation at the top its fundus separated the upper part of the uterus into two horns; it results from incomplete fusion of the Mullerian ducts in the upper parts of the uterine region. The unicornuate uterus has only one Fallopian tube due to failure of the cranial part of one Mullerian duct in the normal way. The septate uterus has normal external features but is characterized by the presence of a septum dividing the uterine cavity into two chambers; it results from incomplete fusion of the two Mullerian ducts.

Development of the External Genitalia

In the indifferent stage of embryonic development of the genital system, it is not possible to differentiate between the male and female embryos on the bases of the appearance of the external genitalia. At the this the external genital is represented by genital tubercle surrounded by two genital folds and two genital swellings in both the male and the female embryos.

The genital tubercle is small, raised tissue in the vicinity of the cloaca. In male embryos under the influence of androgens, it develops into the penis. In absence of androgens in female embryos, it develops into the clitoris. The genital folds which flank the genital tubercle form the prepuce in males by growing ventrally eventually fusing with each other enclosing the glans penis in the second trimester. In females, the genital folds do not fuse with each other as in the male embryo but develop into the labia minora which are folds of the skin which surround the vaginal orifice. The genital swellings of male embryo develop into the scrotum. The developments of the external genitalia of the male and female embryos takes place in a developmental sequence that comprises three stages which are the genital tubercle period, the phallus period, and the definitive period. In the genital tubercle period, the genital eminence has a characteristic conical shape; this phase precedes the formation of the labio-scrotal swellings. The phallus period, which is the second phase begins with the appearance of a swelling called the genital swellings which separate the outgrowing genital tubercle from the surrounding body region; the genital swelling is also called the labioscrotal swelling because it develops into the labia in females and the scrotum in males. The final stage in the development of the external genitalia is definitive period, which witnesses the transition of the components of primary external genitalia into structures that resemble the external genitalia of newborns.

Vaginal canalization is complete in the 5th month of embryonic development and the fetal hymen is formed by proliferation of the vaginal plates (sinovaginal bulbs), which are structures that are formed where Müllerian ducts meet the urogenital sinus. The hymen, which is a membrane or tissue fold that partially or completely covers the vaginal opening, normally becomes perforate before birth or shortly after.

Anomalies of the External Genitalia

Congenital anomalies of the external geniatlia include double penis, hypospadias, epispadias, buried penis, micropenis, ambiguous genitalia, phimosis, paraphimosis, aphallia (penile agenesis), diphallia, female labial fusion, labial hypertrophy, agenesis of the clitoris (absence of the clitoris), double clitoris, septate hymen, and ambiguous geniatlia, where the appearance of the external genitalia is not typically male genitalia or female genitalia.

Comments